THE LEAF MACHINE

Where to begin? Standing underneath a tree seems a good place. A mature tree can have over 700,000 leaves with a surface area the equivalent of three tennis courts. The leaves are like little chemical machines that make carbohydrates, or glucose, to feed the plant. It needs water, light and carbon dioxide to do this. But it doesn’t just mix them all together in a bowl like a cake and out comes food. Each is needed for a different reason. And we must remember that it’s not just big old trees that do photosynthesis. All plants are doing this. The so-called ‘weed’ carving out an existence in a pavement crack on a busy street, is doing photosynthesis too, as are microscopic phytoplankton in the sea.

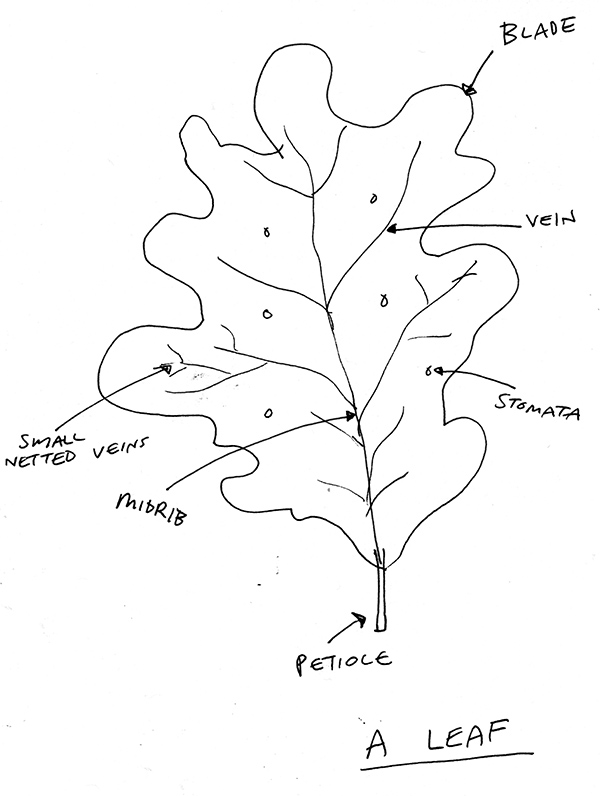

Imagine, if you will, walking across the surface of a leaf (usually called the epidermis). On the underside of that surface, there are tiny openings called stomata (or stoma if we’re just talking about one of them). The stomata allow an exchange of water and gases, which is very important as we’ll see. For our purposes as well, let’s use it as our gateway into the leaf itself. Each stoma has a pair of crescent shaped cells on either side, which change shape and enable the stoma to open and close. They’re also the only surface cells that have chloroplasts.

Beneath the epidermis we go and into the palisade layer. The décor here is lots of regular, oblong shaped cells. I reckon it looks quite funky, but there’s an ordered pattern. These cells do a serious of amount of photosynthesis because they have a lot of chloroplasts. It’s one of these cells that we’re going to explore.

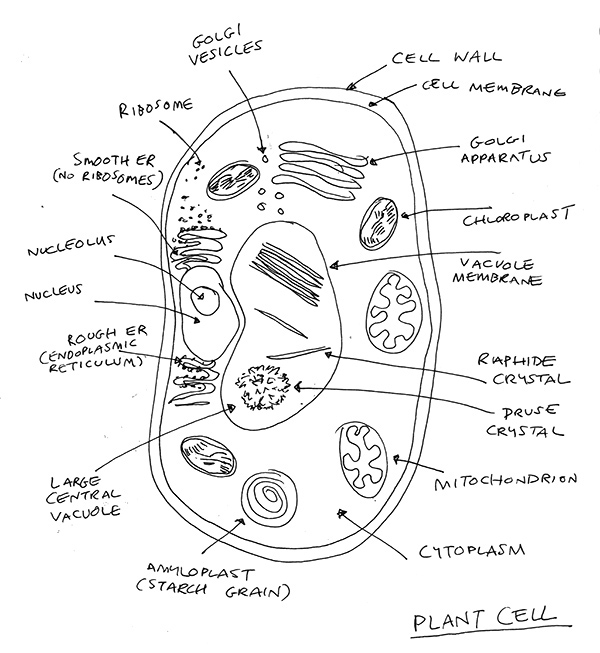

What a beautiful thing a plant cell is. There are hundreds of thousands of these in each leaf. It has a cell wall around it, made of cellulose. This is very different from animal cells which don’t have a cell wall, just a membrane. Plant cells have a membrane too, but the cell walls are important. They give the cells strength and ultimately make trees, and wood, the strong material that it is.

Through the cell wall and here’s the membrane (or plasma membrane). I’m not going to list everything in the plant cell here (see illustration for that!), but we must get through these layers to get to the heart of photosynthesis. The plasma membrane is semi-permeable, allowing some molecules and substances to enter and others to exit. It’s a critical thing, protecting the internal components of the cell from the outside environment.

It’s quite crazy and weird on the other side of the membrane but don’t get distracted. We’re looking for chloroplasts and here’s one. It probably started life as an independent bacteria that could do photosynthesis, and found itself inside a larger ‘eukaryotic’ cell [1]. It’s quite cool to realise that by starting life as a bacteria, the chloroplast has some DNA of its own.

Chloroplasts can come in all shapes and sizes, but this one is sort of kidney shaped. As soon as water – or H2O – enters the chloroplast inside each leaf cell, it is split into separate hydrogen and oxygen atoms in a process called phytolosis. Splitting water might sound easy, but it is fantastically difficult. Humans can just about do it, but it takes a huge amount of effort. At this moment, research is ongoing but without results successful enough to commercialise [2]. Some of the best scientific minds in the world are working out how to do this properly, and here we are standing underneath a tree and above us in every leaf, that process is happening thousands of times a second – silently, seemingly effortlessly.

As far as photosynthesis is concerned, the main players are carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). As we know, these two molecules combined with light from the sun are the three ingredients of photosynthesis, but what exactly is happening?

THE CHLOROPLAST

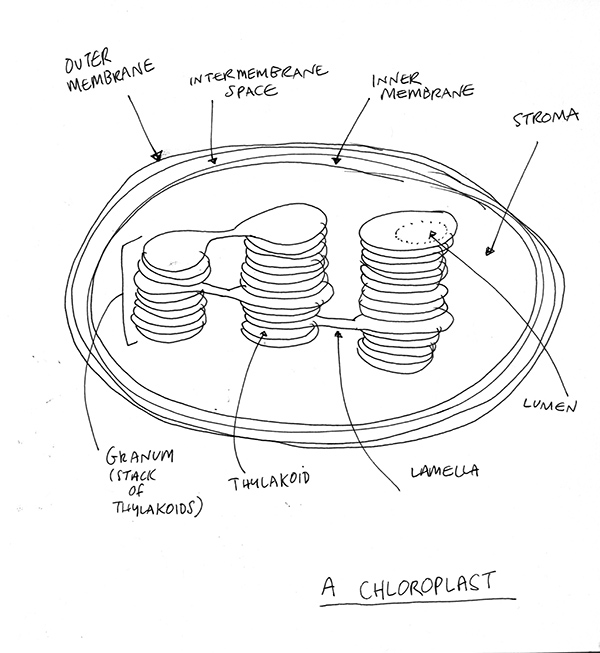

The chloroplast is where it all happens. It’s an organelle within the plant cell. It has its own membrane and can move around inside a cell according to light intensity and direction. It has a liquid inside called the stroma. Within the stroma are tiny structures called granums which are actually stacks of pancake-looking things called thylakoids. These stacks are connected by ‘walkways’ called lamella. It all looks like a futuristic city of some kind.

Each of the thylakoids has its own membrane, called … drum-roll… the thylakoid membrane. Some of the main ‘machinery’ of photosynthesis is embedded within this membrane as we will see in a moment. The interior of the thylakoid is called the lumen. A nice word.

The chloroplast has the ability to split water as we mentioned, but how? This is where light comes in. Light hits a leaf and photons enter the plant cells, reaching the chloroplast and then the thylakoid membrane, where it can be absorbed by chlorophyll.

Chlorophyll is a pigment that can absorb light from the red and blue parts of the electromagnetic spectrum (reflecting light from the green part, which famously gives leaves their colour). It is contained in Photosystem 1 and Photosystem 2 – the simply named parts within the thylakoid membrane where this absorption happens.

Photosystems are light harvesting complexes embedded in the thylakoid membrane with clusters of photopigments – chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and carotenoids. The different chlorophylls (P680 and P700) are to do with wavelengths of light, and carotenoids are probably best known for giving trees their autumnal colours as the chlorophyll withdraws from the leaf. Water is split using energy within light to power the process.

LIGHT DEPENDENT REACTIONS

Photosynthesis happens in two parts, the light reactions and the dark reactions. Both happen in the presence of sunlight so the name is a bit weird. Sometimes they are called light dependent and light independent reactions. The second part is also called ‘the Calvin Cycle’ or more accurately the Calvin-Benson Cycle. The first part happens in the thylakoid membrane. The second part happens in the stroma, the liquid in the chloroplast I introduced earlier.

A quick point about Photosystems. Photosystem 1 was discovered first so it is called 1, but it was later discovered that another Photosystem exists and actually occurs earlier in the process. This Photosystem was named ‘2’, but because it happens first we start there. A bit confusing, but there’s nothing we can do about it.

So, light reaches Photosystem 2. The energy in the light is used to split water, forcing apart the hydrogen and oxygen. The leaf then strips electrons from the hydrogen atom, turning it into a hydrogen ion (or proton). These electrons move their way into Photosystem 2 where they are excited by light and bounce around the system until they reach a special area known as the Reaction Centre. When the electron reaches this point, it gets picked up by an Electron Acceptor (called plastoquinone), which takes it to an Electron Transport Chain (ETC), or cytochrome b6f.

It can help to picture this ETC as a staircase and as the electron goes down the staircase, it gives off energy in a series of ‘redox reactions’.

A redox reaction can be ‘Oxidation’ – the loss of electrons by a substance during a chemical reaction. The substance which accepts these electrons is called the oxidising agent; or it can be ‘Reduction’ – the gain of electrons by a substance during a chemical reaction. The substance which donates these electrons is called the reducing agent.

At the bottom of the ‘staircase’, the electron has given off its energy and is now back in a low energy state, requiring another hit of light in order to be useful. The energy it has just given off is used to create ATP (adenosine triphosphate).

It’s worth noting here that there are two pathways for electrons in photosynthesis. The first is ‘cyclic’ and the electron goes round and round the process just described, creating ATP, which I will describe in a moment. The other pathway is ‘non-cyclic’ and the electron is passed from Photosystem 2 to Photosystem 1 where another hit of light enables it to create NADPH, which I will get to shortly.

Anyway, the creation of ATP is quite cool and a bit convoluted. It’s called photophosphorylation. Remember the hydrogen ion, well there now some of these ions within the thylakoid, in the lumen, and some outside the thylakoid, in the stroma. As the electron goes ‘down’ the ETC staircase mentioned earlier, it doesn’t just give off energy, it also grabs a hydrogen ion (which is a proton) from the stroma and pulls it through the thylakoid membrane and drops it into the lumen (maybe a picture helps… or maybe not!)

The end result of this is that hydrogen ions are building up in the lumen, creating a disparity (or proton gradient) between ions in the stroma and in the lumen. Nature will want to equalise this gradient and ions will want to move back into the stroma. However, they’re unable to just move back through the thylakoid membrane.

This means hydrogen ions are now building up in the lumen, like water behind a dam. The only way back to the stroma is through a mechanism called the ‘ATP synthase’ (anything that ends in ‘ase’ is an enzyme). ATP synthase behaves like a hydroelectric dam. As the ions pass through it, it ‘turns’ and creates energy. This energy is used to turn ADP or adenosine diphosphate into ATP (the D means two phosphates and T means three phosphates). The ATP, thus created by this process, is available to be used by the Calvin-Benson Cycle in the light independent reactions.

Back to the hydrogen ions. The ones that pass through the dam (ATP synthase) are now back in the stroma and go through this cycle again where they are picked up by the electron at the ETC.

There is more going on here though. That’s just Photosystem 2. You might recall the low energy electron which had just been down the ETC. Well, in Photosystem 1 it now gets excited by another photon of light (in the ‘non-cyclic pathway). It goes on a similar journey to Photosystem 2, making its way to another electron acceptor, this time called ferredoxin. Ferredoxin passes the high-energy electron into another ETC (with a crazy name … Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase), but this time rather than being ‘reduced’ and losing its energy, it brings together the electron, NADP+ and a hydrogen ion to make NADPH.

NADPH now takes its electron and hydrogen ion on to the Calvin-Benson Cycle, in order to fix carbon.

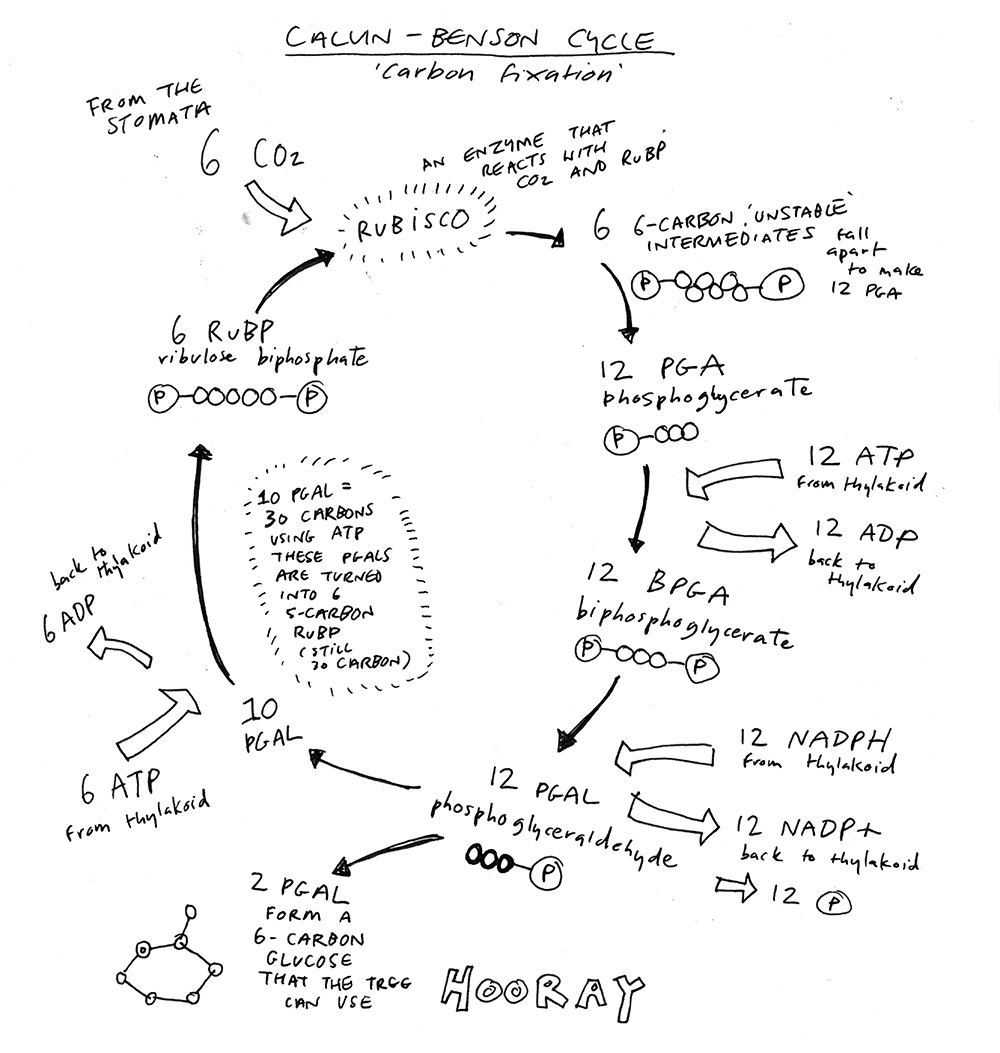

CARBON FIXATION (OR THE CALVIN-BENSON CYCLE)

The Calvin-Benson Cycle is quite something. I said before that leaves are effortlessly splitting water and creating glucose all around us, thousands of times a second. Well, here is where we realise it isn’t effortless at all – it’s very difficult and quite inefficient, even for plants.

All the energy, water and effort required for photosynthesis is mostly used just to make sure the plant can photosynthesise again. It’s a bit like running to the shops to buy food and only ever eating enough so you can run back to the shops again. But every time the photosynthesis cycle revolves around, just enough glucose is created that can be used by the plant and this fraction of useful sugar is enough to create all the plants (including trees), wood and fruit in the world.

Despite the fact that only about one sixth of the process is actually useful for the plant, photosynthesis is still the most amazing process on the planet. Without it, life as we know it is impossible.

Describing the Calvin-Benson Cycle pleasantly is quite hard. What we know is that the plant is now going to turn carbon into something useful – glucose. It needed light to power Photosystems 1 and 2 as we’ve just described. It needed water for its hydrogen and its electrons. It now has ATP and NADPH at its disposal and CO2 entering the leaf through the stomata.

I’ll first quote Oliver Morton’s summary from his book, ‘Eating The Sun: How Plants Power the Planet’: “The key reaction in this cycle is the reaction of carbon dioxide with ribulose biphosphate (RuBP), a sugar molecule containing five carbon atoms, to produce two molecules of phosphoglycerate (PGA); this is the reaction catalysed by the enzyme rubisco. Three such reactions produce six molecules of PGA. The other enzymes involved in the cycle can, if supplied with energy from ATP and NADPH, turn five of these three-carbon sugars into three molecules of the original five-carbon sugar ribulose biphosphate. The sixth three-carbon sugar is ‘profit’ that can be channelled off to the rest of the cell’s metabolism, or stored as starch.”

A pretty succinct outline, but I do wish there was a nicer way to say it. We’re just going to have to dive in. Remember the main equation here 6 CO2 + 6 H20 + light = C6H12O6 (a glucose molecule)? The number six is important – I will come back to it.

It takes place in the stroma, the liquid inside the chloroplast but outside the thylakoid, and is catalysed by enzymes found there too.

Carbon dioxide molecules enter the stroma in the chloroplast and react with the enzyme ‘Rubisco’ to covert ribulose biphosphate (a five carbon sugar molecule, RuBP) into an unstable intermediate six carbon molecule (six carbons with a phosphate at each end). This unstable molecule breaks into two phosphoglycerate (three carbons with a phosphate, known has PGA).

PGA now interacts with ATP and takes a phosphate. This does two things – it turns PGA into BPGA (i.e. there are now two phosphates so it becomes biphosphogylcerate) and it converts ATP back to ADP (because instead of three phosphates, it now has just two). ADP returns to the thylakoid.

BPGA then interacts with NADPH. Now if you recall, at the end of the light dependent reactions, NADPH had a high energy electron and a hydrogen ion. It now donates both of these to BPGA and creates phosphoglyceraldehyde (a three carbon molecule, called PGAL). The NADPH becomes NADP+ again and returns to the thylakoid.

Now two PGALs can join together to make a six carbon sugar that the tree can use. But there is a bit more to it than that. This is where the six becomes important.

It’s not just one CO2 that enters the stroma, but many more. Six is useful because six CO2 react with rubisco and RuBP to make six intermediates. These break in two to create 12 PGAs. 12 PGAs become 12 BPGAs and then 12 PGALs. We need two PGALs to make a six carbon sugar, and that leaves 10 PGALs left over.

Between them these 10 PGALs have 30 carbon atoms (each one is a three carbon molecule remember). By getting energy from more ATP, these 10 PGALs are turned back into five RuBPs. These RuBPs can now be used to keep the Calvin-Benson Cycle going.

So for every turn of the cycle that is useful to the tree, it gets one glucose molecule and five RuBPs. This is the one sixth fraction I mentioned earlier.

Does this explain the C6H12O6 equation? It does if you remember that the 6 H20 (or H12O6) are from the light dependent reactions. You need six molecules of water to donate the hydrogen required for the Calvin-Benson Cycle to work.

So, that’s photosynthesis. Simplify it much more and I think you lose a sense of how incredible it is, but go any deeper into the complexity and it seems to become unfathomable to anyone but an expert.

You don’t have to understand this process to enjoy the fruits of its labour, such as trees, flowers, food, wood, paper, and even fossil fuels in the sense that oil and gas are essentially buried plant matter [3]. Similarly you don’t need to understand the brain or consciousness to enjoy the products of human imagination, such as art, music, cinema, literature and comedy. But if you rely on those products, then it is important to understand where they come from. Understanding leads to appreciation which leads to valuing things. If we (as individuals, as a society, as a species) don’t really understand how photosynthesis works, how the modern world as we all know it would not exist without it, then I think we run the risk of abusing and destroying the very things that make it possible.

Continued in Part 2…

Footnotes:

[1] Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells have a nucleus enclosed within membranes, unlike prokaryotes, which have no membrane-bound organelles.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photocatalytic_water_splitting

[3] Petroleum, also called crude oil, is a fossil fuel. Like coal and natural gas, petroleum was formed from the remains of ancient marine organisms, such as plants, algae, and bacteria. Over millions of years of intense heat and pressure, these organic remains (fossils) transformed into carbon-rich substances we rely on as raw materials for fuel and a wide variety of products. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/petroleum/